News+: That's a wrap

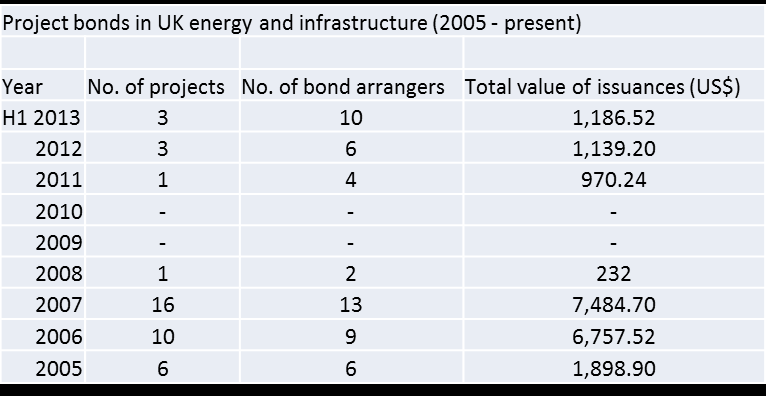

The UK infrastructure debt capital markets have seen an encouraging flurry of deals in the past few months that have emboldened hopes of a renaissance in project bonds.

Once an important source of debt for greenfield developments, the UK project bond market endured a torrid few years following the crisis. Issuances dropped to flatlining levels following the collapse of the monoline insurers who provided financial guarantees known as ‘wraps’ to bondholders, in the process giving borrowers a credit uplift. In their absence, appetite for non-recourse notes from special purpose vehicles (SPVs) evaporated and is only gradually picking up.

As many banks retreat from long-term lending due to impending capital rules, it finally seems that government hopes for institutional investors to fill their shoes through the bond markets are being realised – albeit slowly.

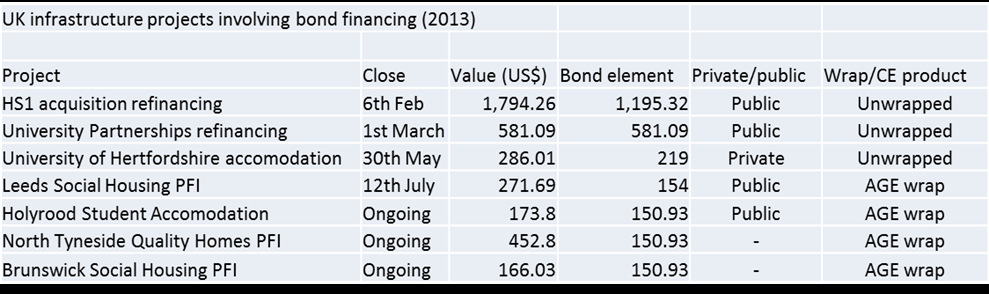

Assured Guaranty's (AGE) recent wrap of a £101.8 million (US$154m) public issue for the Leeds social housing PFI is the first wrapped bond since 2008, by the last remaining infrastructure monoline. It showed a capital market route the market clearly feels comfortable with – and one that procuring authorities believe delivers value-for-money.

The monoline has at least three more deals in the pipeline, covering approximately £400 million of debt. This week Moody’s assigned the Edinburgh University Holyrood student accommodation bond an A2 rating – in line with AGE’s credit profile – on the basis of “credit substitution”.

In parallel, unwrapped issues are staging a comeback. AGE’s re-emergence followed an index-linked private placement for the University of Hertfordshire student accommodation project at the end of May. Insurer Legal & General bought the entire £145 million issue, which came without any form of part-guarantee or credit enhancement.

Significantly, “investors [appear] happy to go down the credit curve to lower-rated instruments, [which] opens up a much wider pool of investment in the debt capital markets for projects seeking capital,” S&P head of infrastructure Mike Wilkins told IJ News.

Wrapped or unwrapped?

So is the greenfield market more likely to go wrapped or not? At play are investor appetite, project sizes and market underwriting capacity.

“[The] larger bond transactions are unlikely to be wrapped because of the exposure limits that monoline insurers have,” predicted Mike Wilkins, adding that larger institutional investors open to big tickets may opt for the higher returns of lower-rated notes.

From a borrower’s perspective, dealing with two or three bondholders in a private placement can make any modifications much easier to obtain than trying to identify potentially hundreds of investors.

But for Dominic Nathan, managing director of AGE, some form of credit enhancement or guarantee means avoiding many of the pitfalls associated with holding construction-phase bonds.

“[Investors] don’t really like BBB- risk on the underlying note and they don’t like controlling the credit themselves,” he told IJ News. “The wrap provides a plug to those holes in investor appetite – construction risk, monitoring the transaction and leverage.”

Projects under construction involve frequent dialogue between developers and funders, for example to authorise drawdowns in the case of payment variations. For smaller investors who lack resources, a benefit of a wrap is that the third party takes care of this.

IJ News understands that AGE has an underwriting exposure of up to £500 million per transaction, with no overall cap. However as the only monoline in town, there is no way it can cover every bond-financed project that comes to market.

This is where the array of competing credit enhancement and guarantee products out in the market may come into its own. All operate on the same basis of either providing a partial guarantee or a subordinated tranche of debt that provides first-loss protection to senior bondholders. Among them are ING Bank’s Pebble Product; the similar Commute product from NIBC, whose differences revolve around the passing over of credit control; and RBS’ construction phase guarantee.

However, there is a sense of frustration that what are essentially state-backed products – namely the UK government guarantee scheme and the EIB’s Project Bond initiative – are crowding out competing commercial solutions by picking the “low-hanging fruit”. With an intrinsically lower cost of capital many feel they should be going for the deals that would otherwise struggle to get over the line. Yet while this was seen as factor in the fall of credit enhancement pioneer Hadrian’s Wall Capital – a £150 million debt fund that aimed to provide a 10 per cent first-loss tranche to uplift the rating of senior bonds – the argument was weakened by the the EIB’s decision this week to debut its product in the refinancing of a gas storage facility in Spain.

In light of recent capital market transactions, the demise of Hadrian’s Wall Capital may not deal such a body blow to project bonds as initially thought. Its innovative mezzanine solution was without doubt impressive, but as rates fell and spreads tightened ultimately it could not compete against banks. In time it may be credited as the intellectual spur for the renaissance of project bonds, but it seems many investors – and procuring authorities – prefer simplicity to complexity.

Project bonds – private or public, wrapped or unwrapped, rated or not – aren’t going to replace banks any time soon. But they can prove complimentary.

Request a Demo

Interested in IJGlobal? Request a demo to discuss a trial with a member of our team. Talk to the team to explore the value of our asset and transaction databases, our market-leading news, league tables and much more.