News+: Real estate or P3s?

In February, officials in Travis County Texas scrapped the idea of engaging in a P3 procurement to construct a new, US$345 million courthouse [Projects Database], and instead, are examining whether a real estate development deal, often called a "63-20" procurement, would be more suitable.

Travis County's change of heart, however, is indicative of a larger problem in the US social P3 market, say P3 deal makers - that engaging in a real estate development deal instead of a P3 can bring problems in terms of risk, cash flow and costs that local government officials may not be aware of.

The 63-20 structure is reportedly being considered to replace several significant social P3s in the US, including the US$1.7 billion Yonkers Public Schools system project [Projects Database], and the US$100 million project to construct the Hidalgo County Courthouse in Texas.

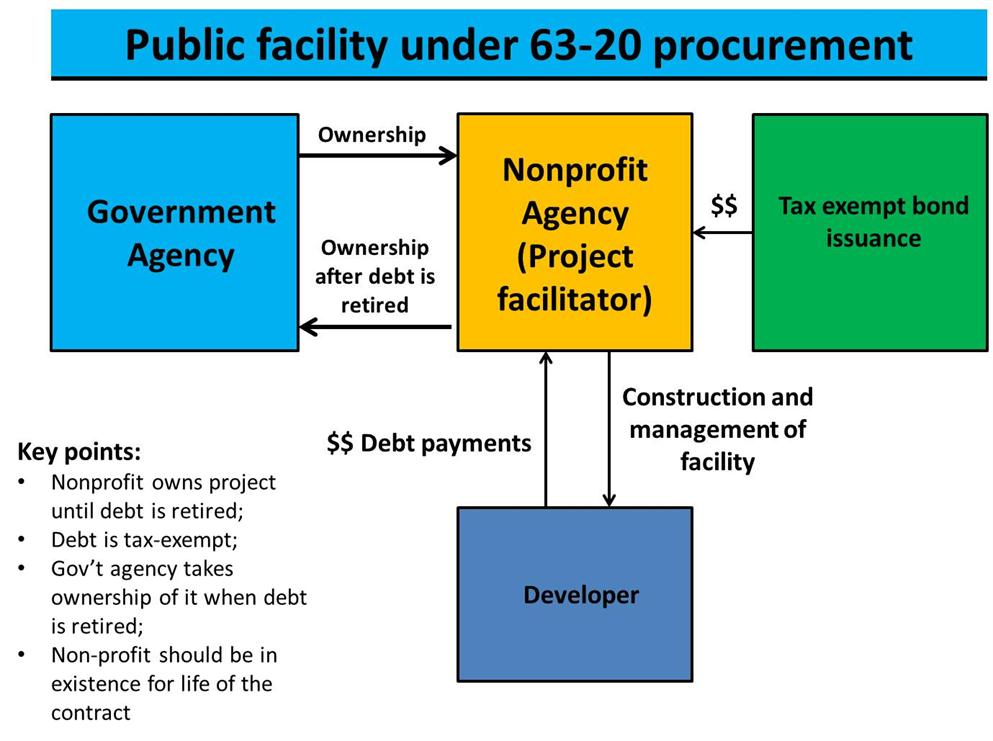

The following diagram shows how the 63-20 structure works:

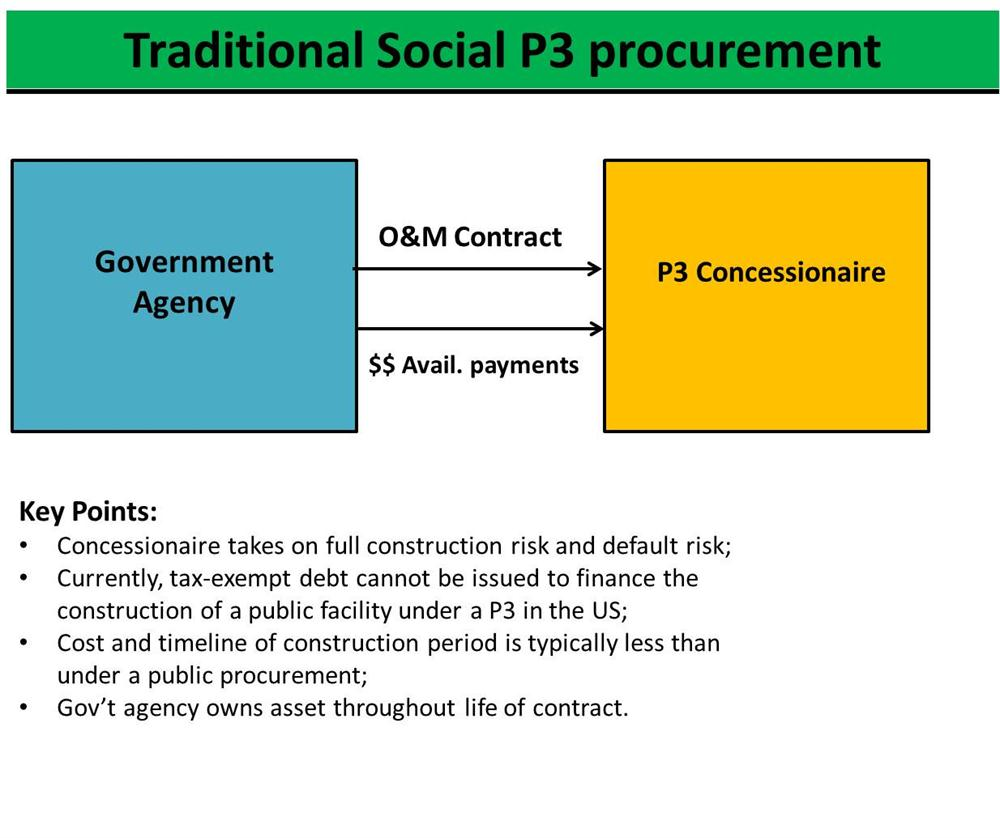

The following diagram shows how the traditional P3 procurement model works:

The California Administrator of the Courts decided last month not to engage in further social P3s after the Long Beach courthouse deal. The main problem, said US P3 executives, is that while the cost of the debt in a 63-20 deal might be cheaper on the surface, hidden expenses can make such a deal more expensive if it is being used in place of a P3 deal. One P3 advisor who did not wish to be identified, said that the accounting practices in a social infrastructure P3 deal could make it cheaper than a real estate development.

“The simple view is that public debt is cheaper,” said the advisor. “Private sector companies in a P3, however, can benefit during economically stressful times when the availability payments are reduced, because then they have the ability to depreciate the asset for tax purposes. When you look at it in those terms, you don’t get a big difference in cost of capital in a P3 versus a 63-20 deal.”

The advisor also said that there is less accountability in a 63-20 deal due to the fact that no one party has equity invested in the asset being built.

“In a DBB process, there is often a lot of of change orders and discrepencies in the cost of capital,” he said. “So the construction phase could end up being more expensive. In addition to the building cost typically being lower in a P3, there’s also a risk transfer (from the public agency to the concessionaire) on the maintenance costs.”

Samara Barend, North America strategic development director for P3s at Aecom, agreed that the lack of equity invested in a project creates risks that are not seen in a traditional P3.

“Basically, in a 63-20 project, developers and engineering firms get together in a sale-lease back deal. The partner is a non-profit, and the equity is basically tax-exempt subordinated debt. It’s essentially a very convoluted way to bring tax-exempt financing in which no party has full accountability,” she said.

Barend is spearheading a lobbying group called the Performance-Based Buildings Coalition, which is pushing for legislation that would allow local governments to issue tax-exempt private activity bonds to fund social infrastructure in traditional P3 deals.

“A 63-20 structure does involve tax-exempt financing but a real estate developer will still own the land,” she said. “What this all comes down to is that the lack of tax-exempt financing for social infrastructure in the US is a big obstacle in this market. The social infrastructure market is going to continue to crawl forward if legislation is not passed.”

One P3 executive said that the difference between a 63-20 deal and a traditional P3 is more fundamental.

“Essentially, a 63-20 procurement is great for a real estate development deal, in which the cash flow is based on leases, and not availability payments,” said the executive. “But when a government agency is looking to construct a public asset and winds up doing a real estate development deal, it opens itself up to increases systemic risk, a less stable cash flow and less accountability in both the construction and maintenance phase. Government officials really need to educate themselves on the difference.”

All-in-all, say US deal makers, it will be key for the US government to pass legislation allowing for tax-exempt debt to be issued to fund the construction and upgrade of public structures. In the meantime, local and state lawmakers need further education on the difference between the two types of deals.

Request a Demo

Interested in IJGlobal? Request a demo to discuss a trial with a member of our team. Talk to the team to explore the value of our asset and transaction databases, our market-leading news, league tables and much more.