Ethiopia’s bold renewable energy ambitions

Ethiopia has huge renewable energy potential. Its government estimates the country to produce roughly 45GW of hydropower alone, though only 5% of this potential has yet been realised.

It is no surprise that the government prioritised renewable energy development in its first five-year Growth and Transformation Plan (2010-15). It set out to increase generation capacity from 2GW to 10GW, though to date only around 4.5GW is operational due to project delays.

The Growth and Transformation Plan II published in 2016 upped that renewable energy target by another 5GW by 2022.

In October (2018), the government unveiled its ambitious $7 billion energy and road programme which included the development of 14 hydro and solar projects with a combined generating capacity of 3GW.

How Ethiopia will fund construction of the projects is in some doubt.

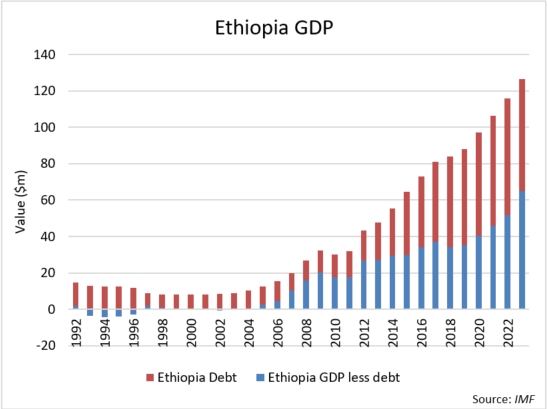

The country has been a grateful recipient of funds via China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). Projects constructed by Chinese firms include waste-to-energy, wind and hydro developments, but rising levels of government debt – in part due to major infrastructure projects – are becoming a concern.

Consequently, the government is hoping to attract greater private investment into its projects. Earlier this year (2018) it announced new PPP legislation that set out the structure of projects procured under this model.

Renewables development across Sub-Saharan Africa has tended to be piecemeal and sporadic. Many countries have turned to project financing – and private investors – to build solar and wind farms, but making projects bankable is a challenge.

South Africa is one country which has had significant success, however. Like Ethiopia, it set aggressive targets for renewable energy generation around a decade ago but has relied far less heavily on Chinese funding to meet its objectives.

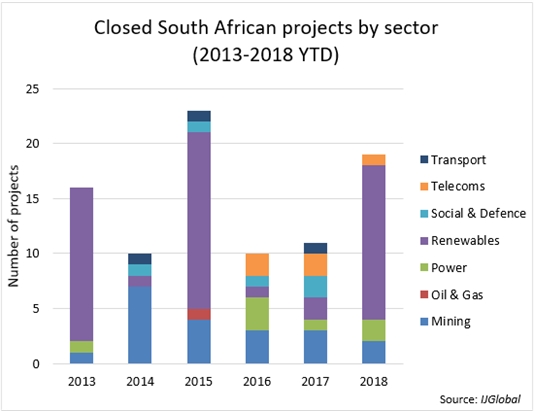

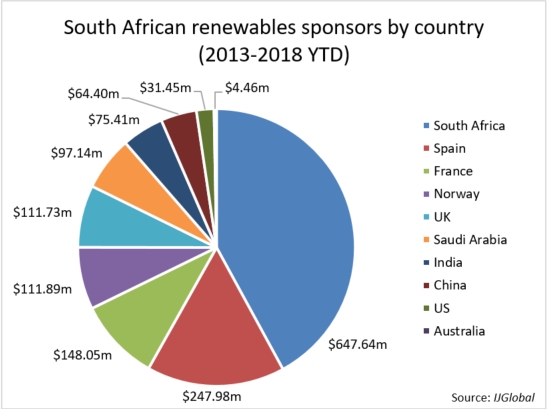

As shown by IJGlobal data, renewable energy has accounted for nearly half of the 168 projects in South Africa since 2013, and these projects have attracted sponsors from a range of countries.

South African companies still account for a significant chunk of the equity invested in these projects, but legal requirements for local content and black economic empowerment make this inevitable. That the country has also attracted so much foreign equity capital, particularly from Europe, is credit to the creditworthiness of its Renewable Energy IPP programme.

Chinese firms have to date only played a very small role in this market.

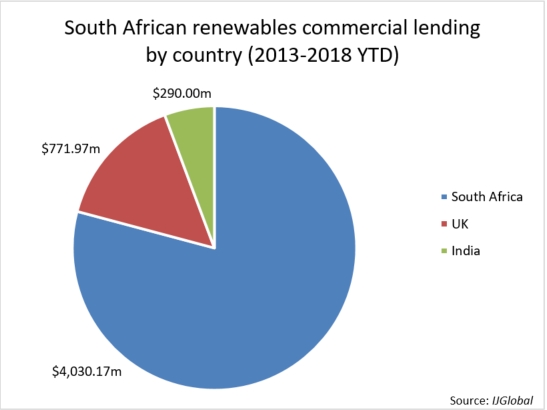

The debt picture is very different. Project revenues are paid in local Rand, and so local banks have a distinct competitive advantage and dominate the market. Some lenders from the UK and India have participated on transactions, but most international banks have neither the Rand reserves nor the appetite to assume foreign exchange risk on such a volatile currency.

Ethiopia may look to South Africa as an inspiration for achieving its renewables goals but there are major differences between the countries.

Though Eskom has had its challenges in recent years, it is much more established than Ethiopia Electric Power or Ethiopia Electric Utility, which have limited experience with PPAs. The grid in Ethiopia is also far less established and in need of significant investment, with large parts of the country not connected to a regular power supply.

Perhaps even more significantly, Ethiopia’s local banking sector has neither the liquidity nor sophistication of banks in South Africa. Ethiopia is likely to have to rely on development finance institutions for the bulk of debt financing required.

Many development banks and the US government’s Power Africa initiative are working to get a variety of independent renewable power projects off the ground in Ethiopia. But it would be truly impressive if the country was able to replicate the success of its Southern African counterpart.

Request a Demo

Interested in IJGlobal? Request a demo to discuss a trial with a member of our team. Talk to the team to explore the value of our asset and transaction databases, our market-leading news, league tables and much more.