China powering into Africa

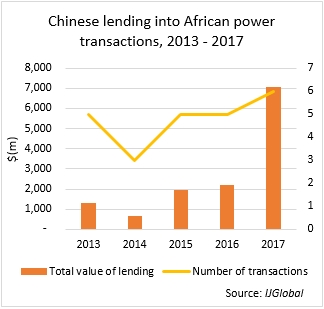

Last year (2017) saw a surge in investment in Africa power assets by Chinese institutions, demonstrating how the continent continues to be of major economic and strategic importance to the Asian superpower.

Chinese state lenders participated in a number of financings for much-needed power projects in Africa, winning a significant market share.

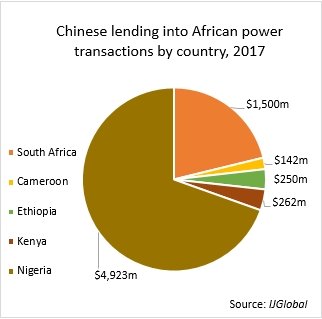

Geographically, the lending has been concentrated into five countries – according to IJGlobal data – with the largest commitments going to Nigeria and South Africa. This is perhaps of little surprise. As the two largest economies in Sub-Saharan Africa, they represent an attractive investment opportunity for lenders with the right risk appetite. Nigeria and South Africa also have huge power demands, which they have struggled to satisfy in recent years.

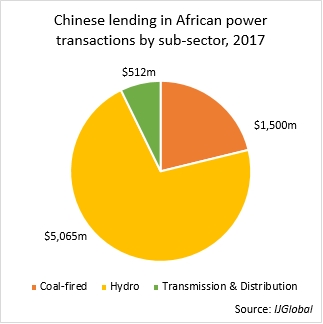

IJGlobal data shows that hydroelectric power has received the biggest chunk of Chinese power financing in 2017. Renewable power projects – principally using solar technology – have started to sprout up across the continent, but the growth of this market is slow and individual developments remain small.

Coal-fired projects continue to be developed across Africa – unlike many other parts of the world, where environmental concerns have made the impossible to finance. And in contrast to solar, the large size of individual projects make them more attractive as investments.

Chinese lending to African coal-fired last year was concentrated in one project: the 4,764MW Medupi power plant being developed by South Africa’s state-owned utility Eskom. The project has long suffered delays, having been in development since 2008, but in July Eskom signed a $1.5 billion loan with China Development Bank to fund its construction.

The flood of Chinese debt follows a 2015 promise by Chinese President Xi Jinping for an increase in Chinese investments in Africa of around 40% by the end of 2018. China’s engagement is also in line with its Belt and Road initiative, which looks to strengthen its economic ties with countries around the world.

Though the borrowers on these projects will have been glad to receive such strong support from Chinese institutions, critics worry that African governments, which are the ultimate guarantor on many of these projects, are being saddled with too much debt.

On the other hand, by helping to boost future power supply in these countries, Chinese lenders should be making a significant positive impact on their economic growth.

And China is filling a void left open by the comparative lack of action from Western lenders.

Launched in 2013, the US government’s Power Africa initiative sought to double access to electricity in Sub-Saharan Africa. Initial success were limited, however, and the new administration in the White House seems far less focused on supporting African development.

Western institutions largely remain cautious about African investment, and any deal with IFC or World Bank backing requires lengthy due diligence to create the level of risk mitigation that many of them require. This puts them at a disadvantage to Chinese institutions which tend to be more flexible and faster moving.

The continent is not only a promising vehicle for geopolitical influence, but its abundant resources – such as oil, copper, cobalt and iron ore – create markets for manufacturers and construction companies alike. Its demographic boom forms expectations of a significant surge in demand not only for power but also for transmission facilities in the years to come.

Chinese institutions look well-placed to continue to profit from the continent.

Request a Demo

Interested in IJGlobal? Request a demo to discuss a trial with a member of our team. Talk to the team to explore the value of our asset and transaction databases, our market-leading news, league tables and much more.