SunEdison behind a cloud

In the last quarter, the self-styled world’s biggest renewables developer has become a toxic stock and appeared to stumble from one crisis to another. In December 2015, SunEdison’s plan to acquire Vivint Solar and sell its residential solar portfolio on to Terraform Power (TERP) came under attack as uncommercial from market observers in general and TERP shareholder David Tepper in particular. Under pressure, SunEdison rewrote the terms of the deal; but Tepper was unsatisfied and is suing SunEdison in court.

Perceived as over-leveraged by analysts and investors, SunEdison has made bids to reduce its $11 billion-plus debt pile, but these too have been criticised. In December again, SunEdison agreed to sell three Hawaiian solar projects to bondholders in return for cancelling $336 million of bonds; this was decried by some as forgoing valuable revenues. In January, it reworked its capital structure further, reducing net debt by $300 million but at the expense of taking on second lien loans with an IRR-challenging interest rate of 11%.

This month, the Hawaiian deal went sour after the projects’ offtaker, Hawaiian Electric, terminated power purchase agreements for all three after losing patience with SunEdison’s delays in getting the projects financed, potentially derailing the sale and the bond cancellation plan with it.

But critics of SunEdison say its problems go back earlier, and have been building slowly over time. For them, what is surprising is that the company’s fortunes have reached a critical pitch as soon as they have.

Balance sheet barriers

Equity has been key to SunEdison’s project acquisition strategy: both new SunEdison equity and equity at TERP, floated in 2014. This made sense when equity was cheap; now that equity markets have become shut to both SunEdison and TERP, their growth strategy is stalled.

Had assets been acquired with a bigger but affordable non-recourse debt component, so the argument goes, this could have been avoided; instead, TERP has been downgraded, SunEdison cannot sell more assets to TERP and both companies’ access to debt is now also constrained.

Another, slightly different view, is that SunEdison’s growth strategy has come at a bad time. “Put simply, SunEdison has tried to run too quickly – seeking hyper growth at the same time capital markets are more challenged – constraining their balance sheet,” Patrick Jobin, an analyst with Credit Suisse, wrote to investors on 18 February.

Shop till you drop

SunEdison was busily acquiring projects in 2015, but some of those deals have been denounced as overpriced. Fresh from acquiring First Wind for $2.4 billion (including $1.5 billion of debt assumed), SunEdison in July 2015 announced that it would buy Vivint Solar for nearly $1.28 billion and that TERP was to buy a wind portfolio from Invenergy for $2 billion, with both deals part-financed by more SunEdison equity.

“The issue with those projects is not that they’re bad projects,” says a financial adviser. “The issue is around valuation. The price that was paid for them no longer makes sense.” Investors in TERP scrutinised the plan to acquire Vivint’s portfolio from SunEdison, and deemed it too expensive. In this view, SunEdison should cancel the Vivint deal and write down the Invenergy portfolio acquisition. But to do so, they admit, would cause a “proverbial run on the bank”.

Michael Morosi, an analyst at Avondale Partners, disagrees and believes the Vivint deal makes sense to SunEdison and TERP. Unfortunately for SunEdison, their failure to resolve the issue has plunged them into a lawsuit that has further degraded investor confidence. Previously, there was talk of SunEdison finding a third party buyer for the Vivint portfolio instead of TERP; this now appears to have stalled.

The human factor

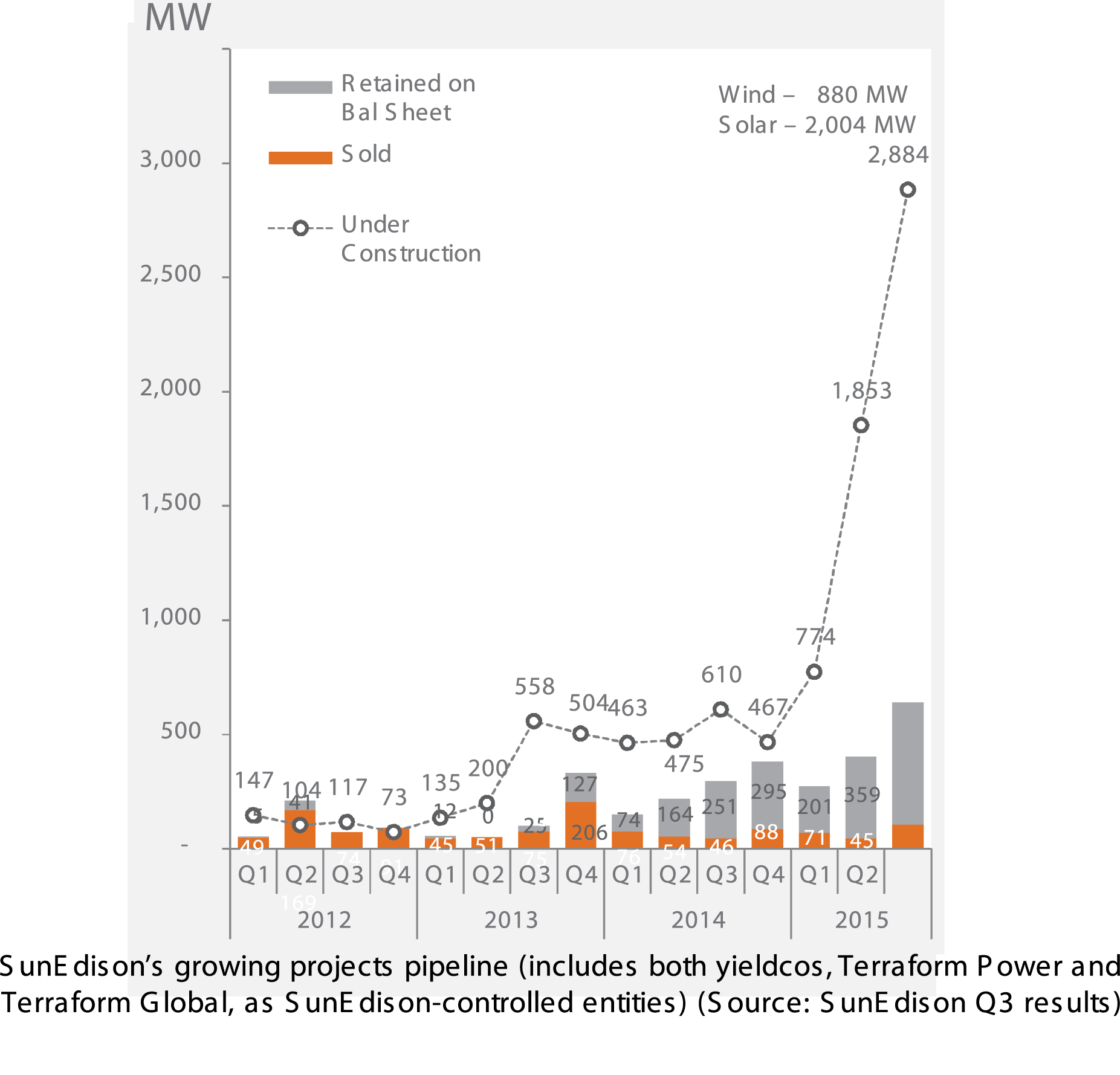

“This lawsuit has significantly distracted that process,” Morosi says, though he is hopeful that SunEdison will weather the storm as its 7.9 GW projects pipeline gets built. “[There will be] pretty significant cash flows in the second half of the year, then they can start harvesting those cash flows… in some respects, time is their friend, but what needs to start happening is fewer distractions.”

But just when this is most critical, SunEdison has been leaking the required expertise to execute those projects. Since December, SunEdison’s chief operating officer, Francisco “Pancho” Perez Gundin; board member Steven Tesoriere; head of North American utility and global wind Paul Gaynor; vice-president of global services Mark McLanahan; and vice-president of finance Manavendra Sial have all left the company. Several of these departures have been linked to a boardroom coup of TERP in December.

“Paul Gaynor was the former CEO of First Wind and was a very competent executive… with particular expertise structuring project finance and execution on large projects. His departure raises potential execution risks on the near-term projects,” Patrick Jobin said. SunEdison will need project execution skills to cure the stricken Hawaiian projects, as well as getting the rest of the 7.9 GW over the line.

While nobody expects SunEdison to fail at this time, serious questions (and the company would not answer any for this article) remain. Will SunEdison persuade banks to lend to its project pipeline at affordable rates? No major financial closes have been announced since September, despite that large pipeline. Will SunEdison’s returns from projects cover its liabilities, as its bond yields climb? And can the board convince investors it has a strategy to monetise assets? The questions remain open for now.

Request a Demo

Interested in IJGlobal? Request a demo to discuss a trial with a member of our team. Talk to the team to explore the value of our asset and transaction databases, our market-leading news, league tables and much more.