News+: Dry powder in the chest

Brookfield’s final close on its colossal US$7 billion infrastructure fund underscored a market bulging with dry powder.

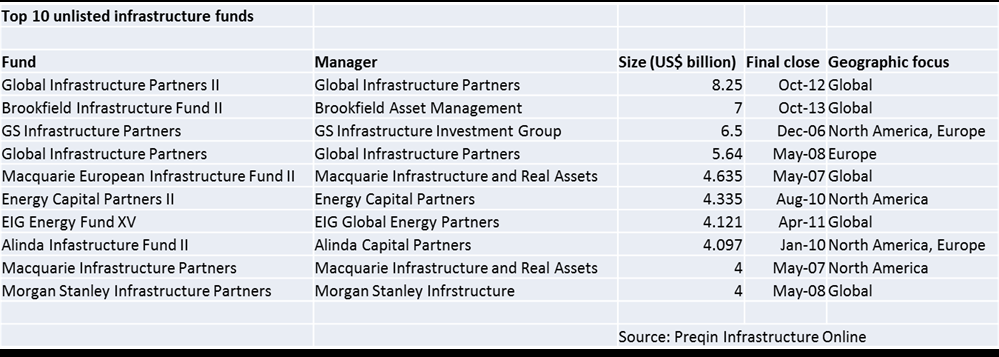

The Toronto-based manager outstripped expectations last week – not least its own US$5 billion target – as it clocked up the second-largest unlisted infrastructure fund to date, behind only the gargantuan US$8.25 billion effort that Global Infrastructure Partners wrapped up just over a year ago.

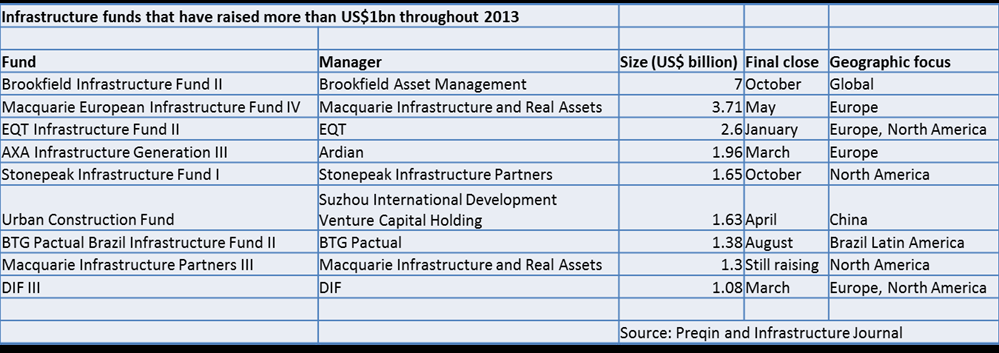

It also became the ninth infrastructure fund manager this year to reach a fundraising close above the prestigious US$1 billion mark.

On the road

The fundraising was all the more remarkable in that Brookfield spent just 11 months on the road: not only less than half the average time it takes infrastructure fund managers to conclude capital raising today, but even a month quicker than it took on average in the frothy pre-crisis days.

Commitments from limited partners (LPs), who numbered more than 67 in the final mix, snowballed in the first half of the year: a regulatory filing revealing that managers had garnered US$6 billion by July. For half of those investors it was their first time in a Brookfield fund.

One industry source said that part of Brookfield’s success could be attributed to the fund manager’s “quite unusual” approach of putting so much of its own money into its funds – in this case writing a cheque for US$2.8 billion. “The alignment of interests between manager and investor is much greater,” they commented.

Smaller and fewer

The enormous success of GIP and Brookfield over the last year belies the trend that infrastructure funds reaching final close are, on the whole, smaller and typically in number today compared to pre-2009 levels – despite a record number of managers in the market. Preqin’s data shows that most of the top 10 infrastructure funds of the last decade are of a pre-crisis vintage.

At the same time there is mounting evidence of what industry players call a “birfucated market”, where the spoils are concentrating in the hands of a few big names, with smaller and first-time managers left scurrying in their wake. With many firms now raising second and third-generation funds, past performance is a key consideration in manager selection and investors scrutinise actual versus targeted returns closely.

Amid large inflows of capital heating up the brownfield infrastructure sector, the real challenge now for big ticket managers like Brookfield lies in spending it wisely.

Dry powder

Total ‘dry powder’, investment parlance for committed capital waiting to be deployed, stands at a record US$93 billion in the infrastructure fund market, according to data from Preqin. This is US$23 billion – or 33 per cent – higher than the figure in December 2010, giving rise to the common refrain that there is too much capital “chasing too few assets”.

Coupled with the increasing number of sovereign wealth funds (SWFs) and large institutional investors looking to get more bang for their buck by investing directly rather than through the intermediary of funds, it all adds up to a lot of fire power.

“It’s definitely going to be very competitive,” said Mike Newell, funds partner at law firm Norton Rose Fulbright. “There’s plenty of capital for the actual assets that are there, but people will find more assets to bring onstream.”

Infrastructure M&A processes of recent years bear testament to this. Prized assets like UK water companies, busy passenger airports and European power grid networks have witnessed bids at increasingly high multiples of earnings, as investors flock to their relatively safe and stable cashflows.

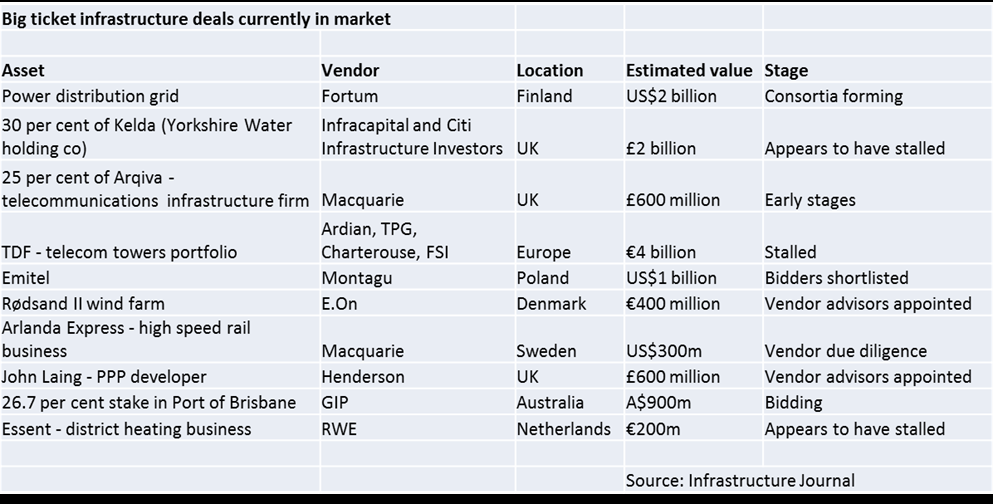

Compounding the competition is the scarcity factor. Big deals have been slow in coming to market over the last 12 months. The stalled £2 billion sale of a 30 per cent stake Yorkshire Water by Citi Infrastructure Investors and Infracapital, for example, is symptomatic of a sluggish infrastructure M&A market.

“It’s a bad market as there are not many big deals to invest in,” says Hans-Peter Dohr of DC Placement Advisors, which acts on behalf of funds marketing in Europe. “Managers will start looking outside utilities and energy into other sectors like telecommunications [infrastructure]”.

M&A resurgence?

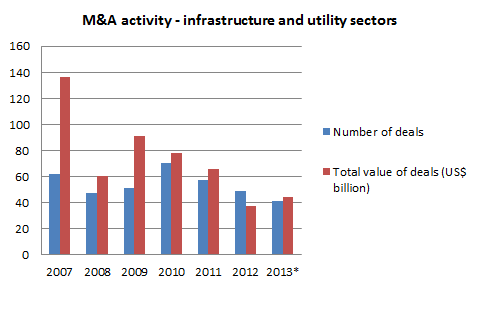

Analysis by law firm Allen & Overy of infrastructure and utilities M&A activity shows the aggregate value of global deals in 2013 so far is US$43.99 billion, already 17 per cent higher than the 2012 total (US$37bn), yet still leagues away from the 2007 zenith of US$136.65 billion.

Source: Allen & Overy

But a closer inspection reveals that 30 per cent deals of the 13 deals (worth US$9.56 billion) that closed in the third quarter involved Chinese targets and Chinese acquirers – a jurisdiction most funds don’t have a mandate to go near. Stripping these out, Q3 deals were at their lowest since 2008.

A glimmer of hope is on the horizon as the first generation of infrastructure funds – which closed between 2002 to 2005 – start to recycle assets, with the likes of Macquarie, Alinda and Citi all starting divestment processes.

While seeing “little evidence of an abundance of deals in the pipeline over the short term” in Europe, A&O found reason for optimism with the prediction that “a resurgence in deal activity may just be around the corner.”

A competitive world

All other things being equal, the law of supply and demand dictates that yields will be squeezed as prices keep rising – a situation that favours investors with a lower cost of capital, such as SWFs.

A watchword for infrastructure fund managers in the M&A market is discipline. This consists of neither bidding too aggressively – and inadvertently strangling final returns to investors – nor rushing to buy assets simply to get capital deployed. No easy task given that general partners (GPs) are under pressure to deliver yield from day one.

Request a Demo

Interested in IJGlobal? Request a demo to discuss a trial with a member of our team. Talk to the team to explore the value of our asset and transaction databases, our market-leading news, league tables and much more.